Cette publication est également disponible en :

Français

Speech by Saverio Campanini

Sepher Yetzirah symposium

“Liber formationis […] docet sic novos formari homines.“.

Ludovico Lazzarelli

In 1536, in his In Scripturam sacram Problemata, three thousand exegetical questions on the Bible, the Venetian Franciscan Francesco Zorzi asks why, of the two million Israelites who received the law on Sinai, only two will enter the holy land. Moses is not among the chosen ones, but Joshua and Caleb, as we know. The second attracts his attention: what special merit does he have to receive the rare privilege of being able to enter the sacred domain after forty years of wandering in the desert? Is it, the Franciscan wonders, due to the fact that, as we read in the book of Numbers 1 Numbers 14:6. and a second time, more precisely in the book of Joshua 2 Joshua 14:7-10. he is the only one, along with Joshua himself, who remained faithful to the divine word, who sincerely described the promised land he had already traversed with the explorers? This is precisely what the biblical text gives us as an explanation for this particular election among the chosen people. Zorzi, however, does not stop his exegetical research there. He asks: if there is a deeper reason for the exception, it is conveyed in the names of these characters. Caleb is interpreted, according to the etymology already suggested by Saint Jerome in his Liber interpretationis Hebraicorum nominum, as “totus cor”, “whole heart” or “all heart”. And the heart of those who are to enter the kingdom of God must be entirely pure and faithful. So far, we’re in the spiritual tradition of moral allegorism based on an ancient etymological tradition. But Zorzi doesn’t stop there: he observes that the name Caleb, analyzed as Kol Lev, contains the word לב, whose numerical value is 32. It becomes natural for him to quote “Abraham” according to whom God created the world by 32 paths of wisdom. This means, according to the Franciscan, that we can enter the promised land through the 32 paths of wisdom that God has placed in the heart, and from the heart these paths enable us to understand the world and transcend it. 3 F. Zorzi, In Scripturam Sacram Problemata, Bernardinus Vitalis, Venetiis 1536, tomus I, sectio VII, f. 52r-v, problema n. 405: “Cur Iosueh tantummodo et Caleb singulari privilegio in promissam terram intrarunt? An, quia ambo Deo confisi fideliter tetulerunt: quae in terra illa exploraverant, ut aperte de Calebb loquitur textus? An (ut ab sublimius sensum conscendamus) intrat in terram illam Caleb, qui totus cor interpretatur: ille videlicet, qui toto corde Deo inhaeret: aut qui habet totum cor mundum? Quod Deus potissime requi- / rit. Sicut ipsum cor magno artificio fabricavit. Core nim hebraice לב dicitur, quod trigintaduo in numero importat. Iuxta trigintaduas semitas sapientiae: quobus (ut Abraham ait) Deus mundus creavit. Ad quas semitas potest cor nostrum ascendere, sicut Propheta canit: Ascensiones in corde suo disposuit [Ps. 83,6]. Est quoque binarius cum tricenario numerus iustitiae, in partes aequales semper usque ad unitatem divisibilis. Quam iustitiam sequi debet illuc intraturus. Intrat quoque Iehosuah, qui salus vel salvatus interpretatur, idest ille, cui Deus dat salutem, vel qui se disponit ad illam consequendam.” The Liber formationis is cited here as written by Abraham the patriarch, and is referred to as a wisdom tradition that a Christian can and should use to understand the intricacies of Scripture. What I intend to show today is how it was possible for an esoteric text from the Jewish mystical tradition, which was completely unknown fifty years before, to become an obligatory reference in the exegetical practice and meditation of a pious friar like Francesco Zorzi and in the works of many other Christian authors in the Renaissance and beyond.

The date of composition of the Sefer Yetzirah is controversial, but in any case it seems that hardly anyone in the Christian world had heard of it before 1486. Among the earliest mentions is the Monstrador de Justicia by the convert Alfonso de Valladolid, who, in the 14th century, following the miracle of Avila (in which a rain of crosses fell on the city’s Jews who were awaiting the imminent arrival of the Messiah) and after a vision in a dream, relates that he used the method presented by “the author of the book called Cefer Yeçira“, according to which “tres piedras facian ses casas” (three stones make six houses). 4 I. Loeb, Polémistes chrétiens et juifs en France et en Espagne, in “Revue des études juives” 18 (1889), pp. 43-70: 56; F. Secret, Les kabbalistes chrétiens de la Renaissance, Dunod, Paris 1964, pp. 14-15; Alfondo de Valladolis (Abner aus Burgos), Monstrador de Justicia, Hrsg. Von W. Mettmann, Bd. I (Kapitel I-IV), Westdeutscher Verlag, Opladen 1994, pp. 14. It’s true that the text of the Monstrador remained unpublished, but Alfonso de Spina’s Fortalitium Fidei draws on several of his works (even those which, like the Book of the Lord’s Wars, are lost in the original Spanish), although, if I’m not mistaken, he didn’t include mention of the Sefer Yetzirah.

In any case, reading the preface to Mosheh Bottarel’s Commentary on the Sefer Yetzirah, we learn that this work was written for a Christian, Maitre Juan, whom François Secret considered “mysterious”. 5 F. Secret, Pico della Mirandola e gli inizi della cabala cristiana, in “Convivium” $ (1957), pp. 31-45: 44;Id, Le Zohar chez les kabbalistes chrétiens de la Renaissance, Durlacher, Paris 1959, p. 25; Id, Les débuts du kabbalisme chrétien en Espagne, in “Sefarad” $ (1957), pp. $$-$$: p. 25; Id, Les kabbalistes chrétiens de la Renaissance, cit, p. 16. . However, it seems highly likely that this Christian was a convert: Maestro Juan el Viejo de Toledo, born in Villamartì and author, in 1416, of a treatise against the Jews(Memorial de los misterios de Cristo) preserved in numerous manuscripts but only recently published, 6 It was edited by Manuel Jesus Acosta Elias, in his doctoral thesis El Memorial de Juan el Viejo de Toledo. Edición del Texto Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia, 2018. On p. 58: “E dice Dios: Alabará la su palabra, que es el su saber [Ps. 56,10]. E así le llamó en el libro que es llamado Cefer Esra [but we should prefer here the variant: Cefer Yeçira du ms. 1776 de la Biblioteca General Histórica de la Universidad de Salamanca] e tienen los judios que lo fiso nuestro padre Abrahán. Llama a la sabiduria de Dios palabra e concuerda con el dicho de San Juan en los santos Evangelios: “In prynçipio erat verbum” [John 1,1]. while another treatise by this baptized rabbi dedicated to the exegesis of Psalm 72 remains unpublished. There can be no doubt that Juan de Toledo used the Sefer Yetzirah, among many other rabbinic and medieval sources, to convince his co-religionists to accept the Christian faith, as he had done in 1391 following Vicente Ferrer’s preaching.

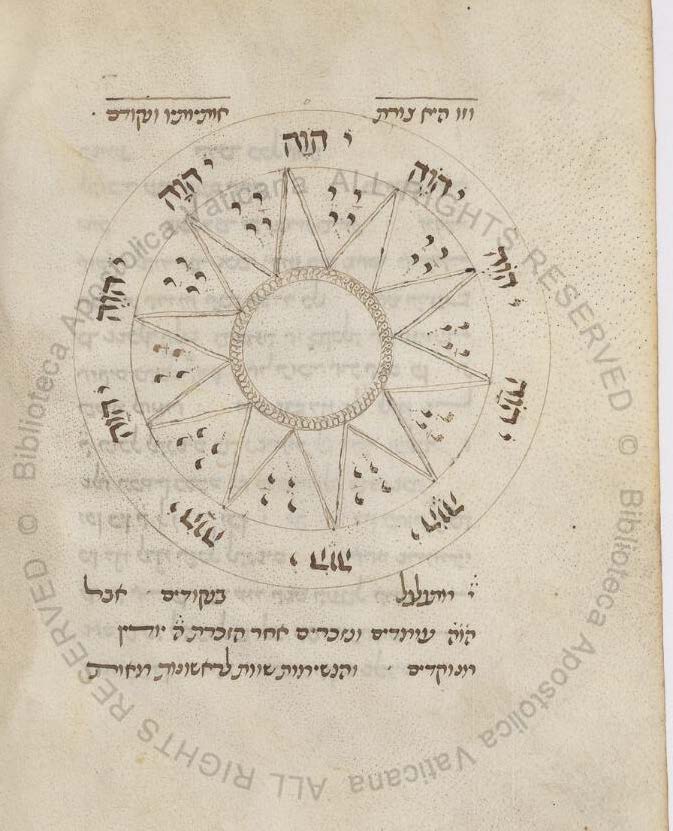

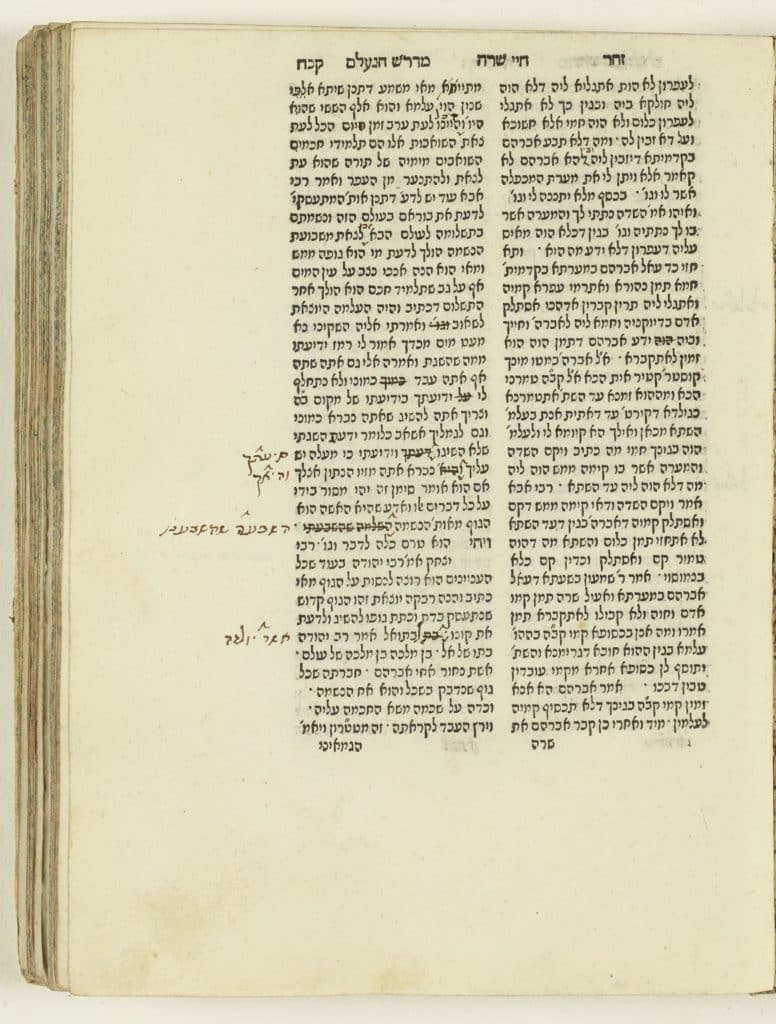

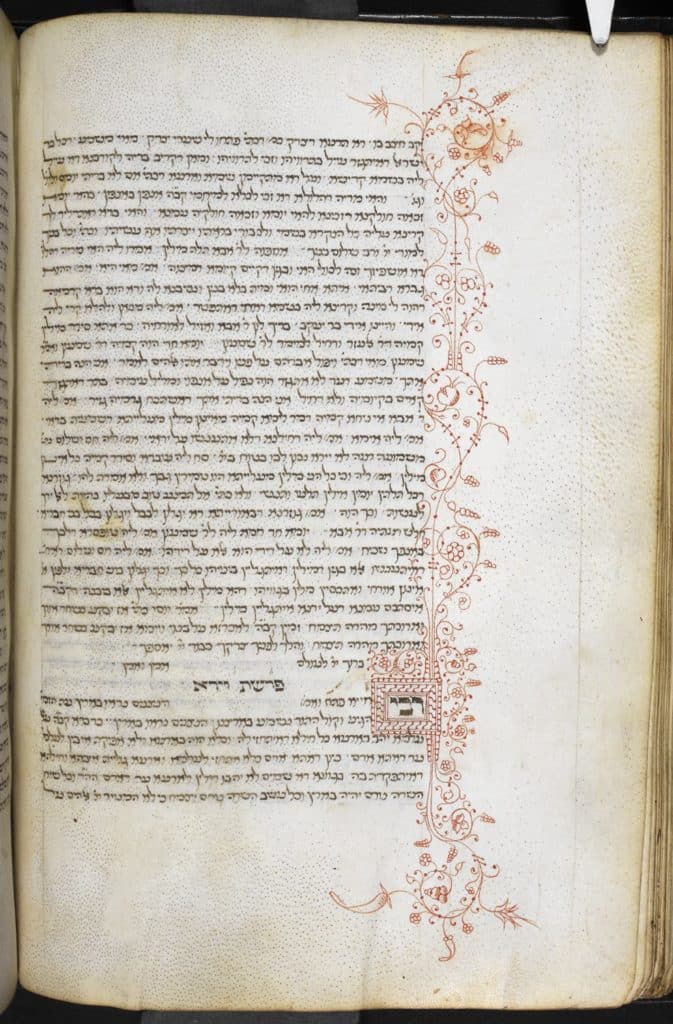

If the first mentions of the Sefer Yetzirah among Christians took us to Spain, in the fiery climate of religious controversy at the end of the 14th century and the first half of the 15th century, for the first Latin translation of the book we’ll have to wait until the end of the 15th century and go where all roads lead, i.e. to Rome, in 1488. In fact, it’s very likely that another Latin translation of the Sefer Yetzirah was completed before this date, most likely by Flavius Mithridate for Count Jean Pic de la Mirandole in or before 1486. It’s very likely that Mithridate translated the Sefer Yetzirah for Pico, but among the thousands of folios translated from Hebrew into Latin, this work is missing, for whatever reason. We can only speculate as to why the Latin Book of Creation is missing from the preserved cabalistic library. It is perhaps interesting to note that, in the ms. Vat. Ebr. 191, just before a series of several commentaries on the Sefer Yetzirah, four pages are missing, as is evident from a jump in the numbering of the leaves. It is very likely that the “booklet” was detached from its place to be given to copy or to study separately. On the other hand, the same manuscript contains no less than four commentaries on the Sefer Yetzirah, translated from Hebrew into Latin: the commentary by El’azar of Worms, the “anonymous” commentary of the Abulafian school, another anonymous commentary and the authentic commentary by Ramban, the one published by Gershom Scholem in the original Hebrew on the basis of a Leiden manuscript, and a fourth commentary that still resists identification. In any case, from these commentaries, as well as from the numerous quotations from the Sefer Yetzirah in other Kabbalistic works also translated by Mithridate and whose translation is preserved, we can easily reconstruct, albeit in an approximate manner, a hypothetical translation by Mithridate that may have been the first Latin translation of the Sefer Yetzirah.

In any case, having collected the fragments of this virtual translation made by Flavius Mithridate, I can assure you that this translation has nothing to do with the one made in Rome in 1488, found in two manuscripts (one in London and the other in Bergamo) and published in 1587 by Johannes Pistorius in his famous volume Artis cabalisticae scriptores, published in Basel by Heinrichpeter. This first volume was never supplemented by the promised second, which should have included Latin translations of other cabalistic texts. In any case, Pistorius, who had access to Reuchlin’s library in Durlach, must have used the ms. Add. 11416 but he was not particularly careful, as soon as he misinterpreted the ms, For example, and most strikingly, he read the incomprehensible “cabalistinis” instead of the very clear “cabalisticus” which reads in the ms. Furthermore, he omitted a rather interesting piece of information, which reads in both manuscripts, albeit more or less completely: the ms. currently preserved in London informs us that the translation was made by a “magister Isaac” in Rome in 1488, while the Bergamo ms. later specifies that it was Pentecost. Although this translation was not the first to appear in print (as we shall see, that honor is reserved for Guillaume Postel’s translation), it had a remarkable impact and is quoted very often, apparently even by Jean Pic de la Mirandole’s nephew, Jean-François. It is unlikely, however, that it was executed for Pico, since he already had a translation, as has been assumed, and, above all, was not in Rome at the time.

The question arises as to the identity of this Magister Isaac, who translated the Sefer Yetzirah for Christians in Rome under the papacy of Innocent VIII, and a number of hypotheses have been put forward: among others, a Jew named Isaac, mentioned by Gianfrancesco Pico in a letter to Sante Pagnini, who was converted by Gianfrancesco’s uncle John Pico della Mirandola and became a Dominican friar under the name of Clemente Abramo. Another hypothesis, formulated by Franco Bacchelli. 7 F. Bacchelli, Giovanni Pico e Pier Leone da Spoleto. Tra filosofia dell’amore e tradizione cabbalistica Olschki, Firenze 2001, pp. 98-100. suggests identifying the “Magister Isaac” translator of the Sefer Yetzirah with the son of a Provençal Jew who was in contact with Pico della Mirandola, Jochanan Alemanno, and whose name was Isaac. As we mentioned a moment ago, it doesn’t seem likely that Pico could have been directly responsible for this translation, but the game of suggestions and hypotheses could go on for a long time yet: for example, we could imagine that the Magister Isaac in question should be identified with the physician Isaac Zarfati, who later became personal physician to Pope Clement VII and who, in 1530, was 70 years old. There is no reason to suppose that he could not have been the author of this translation, which must have circulated in Curia circles. Unfortunately, there is no evidence, solid or weak, to prefer this identification to the others, apart from the fact that Isaac Zarfati was a physician and, as such, could have been interested in this proto-scientific text and, perhaps, in making a name for himself among the doctrines surrounding the pope, in the city where a Spanish convert Pablo de Heredia published his Epistola de Secretis, probably during the same year 1488. The truth is that there were too many “Magistri Isaac” in Rome at that time and a little later to hope, by simple onomastics, to be able to identify him, I only recall here the Isaac ben Abraham of Galilee, who, in 1513, copied a Sefer ha-Zohar (now at the Casanatense) for Gilles of Viterbo, or the little-known Spanish physician Isaac, who wrote a poem in Hebrew in praise of the De arcanis catholicae veritatis by Pietro Galatino, published by Gershom Soncino in 1518, or, if not the same, an Isaac de Toledo who was a protégé of Leon X Medici. What seems to me less sterile than the “who’s who” game in this case is to ask the question “for whom” this translation was made. In his Hebrew poem, the Spanish physician “Isaac” mentions Reuchlin indirectly, as soon as he names the Cologne inquisitor Jacob Hoogstraten, who in Galatino’s De arcanis played the role of Reuchlin’s adversary (Capnion). This could explain the presence of the translation among Johannes Reuchlin’s books, despite two weighty objections: Reuchlin, who had visited Florence in 1482, did not arrive in Rome until 1490, but, as far as we know, he was not yet interested in Jewish studies. He returned to Rome for the last time in 1498, and it may well have been on this occasion that he acquired the translation, which in any case could not have been made for him. The fact that another copy of the same translation survives in Bergamo demonstrates, if proof were needed, that it circulated among humanists. The second difficulty is even more serious when, if we compare the passages from the Sefer Yetzirah that Reuchlin quotes in his De arte cabalistica, published in 1517, he never uses Master Isaac’s translation. In any case, Magister Isaac’s translation was in his library right up to the time Pistorius used it for his anthology. One might even suspect that he borrowed it and forgot to return it. What is certain is that the manuscript, which also contains Joseph Gikatilla’s Ginnat Egoz, was no longer in Durlach when Johann Heinrich Mai wrote the catalog of Reuchlin’s library. It was already, at least from 1624, among the books of Sobernheim monk Otto Gereon. Later, according to Johann Christoph Wolf, the book was in the library of the Calvinist theologian Johannes Braun, appearing in Paris in the first half of the 19th century as part of the legendary collection of A. A. Renouard, before being purchased by the British Museum at the Evans sale of 1838. Now, part of the book was given as a gift to Reuchlin by Johann von Dalberg, Bishop of Worms, who notes the date (April 1495), but the hand that copies the “Liber de Creatione” is Reuchlin’s own, meaning that, if he had copied it in Rome in 1498, he later bound it with Gikatilla’s Ginat egoz and with other scattered material, such as a letter from Trithemius in 1499. The current situation of the manuscript does not allow us to speculate on the origin of this translation, nor on its original recipient(s). We may assume that the physician Pierleone da Spoleto, who was in contact with Pico and took a keen interest in the cabala, copied other cabala works, 8 Cfr. S. Campanini, Questa e la cabala certa et fortissima et miravigliosa. Testi cabbalistici dalla biblioteca di Pierleone da Spoleto in S. Graco – J. Olszowy-Schlanger (edd.), Counting the Miracles: Jewish Thought, Mysticism, and The Arts from Late Antiquity to the Present, De Gruyter, Berlin 2025, pp. 459-520. for example, part of Manachem Recanati’s commentary on the Pentateuch (now in Genoa) 9 S. Campanini, Un frammento della traduzione latina del Commento al Pentateuco di Menachem Recanati compiuta da Flavio Mitridate per Giovanni Pico della Mirandola. L’excerptum di Pier Leone da Spoleto in M. Andreatta – F. Lelli (edd.), ‘Ir ḥefṣi-vah. Studi di ebraistica e giudaistica in onore di Giuliano Tamani Belforte, Livorno 2020, pp.219-314. and one of the commentaries on the Sefer Yetzirah translated by Mithridate (Pierleone’s copy is preserved in ms. Vat. Lat. 9425), 10 Cfr. M. Ficino, Lettere, vol. I, a cura di S. Gentile, Olschki, Firenze 1990, pp. LXXXI-LXXXII; Bacchelli, Giovanni Pico, cit. p. 4. Pierleone’s copy is, in fact, an excerptum, since it includes only the text from ff. 12r to 19r. could also be the source of this translation. We can easily assume, in fact, that he was familiar with the translation of Mithridates and are even certain that, at least in the form of an annotated version, he had it at his disposal, and what’s more we know, thanks to Franco Bacchelli’s research, that he had another Latin translation at his disposal, which may have been completed shortly before or even in 1488. This translation, published only in part, is contained in ms. 868 of Florence’s Biblioteca Riccardiana, and all the works included in this dummy collection date from the years between 1478 and 1492. The collection belonged to Mazzingo Mazzinghi, a Florentine physician, pupil of Pierleone da Spoleto and later personal physician to Marsilio Ficino. The copy in ms. Riccardiano is in Mazzinghi’s hand. Without having identified with certainty two of the authors of these translations, we can conclude that, between 1486 and 1488, at least three different Latin translations of the Sefer Yetzirah were completed for Christian readers who, starting from Pico’s proclamation that the texts of the cabala and the Jewish mystical tradition confirm the truth of Christianity, there have been repeated attempts to seize upon a key text, quoted everywhere not only – as is obvious – in commentaries, but also in cabbalistic literature, the object of desire in this season of humanism in Rome and Florence. The function of translations is not simply to enable the text of the Sefer Yetzirah to be read by Christians who did not have access to the original Hebrew. In the specific case of the Sefer Yetzirah, as I’m going to show straight away with a selected example, it’s an addition to the vast library of commentaries on the Sefer Yetzirah in Hebrew and Arabic, because its extreme synthesis and bold formulas demand commentary, forcing the reader, even the Hebrew-speaking reader, to pause at every line and, sometimes, at every word, to try and understand what the author, whether Abraham, Rabbi Akiva, or a later anonymous person, meant. The fact that the Sefer Yetzirah underwent a large number of commentaries from the 10th century onwards is well known and, for example, Abraham Abulafia, in a text that was also translated for Pico della Mirandola, claims to have studied twelve of them. The Latin translations – the first, as we shall see, of those produced and, in part, published in the 16th and 17th centuries – should be considered as belonging fully to the genre of commentary.

In an attempt to explain myself better, I have chosen one of the most discussed passages in the booklet, the first mishnah (doctrine) of the first chapter, to show how the versions, although produced at the same time, by converts or by Jews in close contact with the same intellectual circles, differed from one another in remarkable ways. Here, I shall confine myself to showing how different translators understood the triad of “sefarim”. It’s already problematic to give the original, because vocalizations are variable, but, say “God created his world with three sefarim : with sefer, sefar we-sippur” (ספר ספר וספר). I spoke of three translations: the (extrapolated) one by Mithridate (1486); the one by Magister Isaac (1488) and the anonymous one by Pierleone copied by Mazzinghi, but in reality on this paragraph at least, we have four, because in the margin of this last version, an alternative, called “alia litera”, which is also a characteristic of Hebrew manuscripts, to annotate variants (nusach acher) in the margin. According to Mithridate, the three sefarim are to be understood as liber, numerus seu numeratio, and numerabile seu numeratum ; according to Magister Isaac the three are: scriptis, numeratis, pronunciatis ; according to the main text of the anonymous translation for Pierleone, we have, more abstractly, but not far from the preceding, scriptura, numerus, elocutio ; in the margin, with the addition et credo quod sit verior; which may come from the translator but also from the addressee/copist, we read: conceptus, ratio et sermo. I’m in no way proposing to choose between these alternatives, which in some cases are more appearance than reality, but I will nevertheless note that, perhaps with the exception of the last two translations, of which the second appears to be a correction and polished version of the first, and in any case they come from the same pen, the three/four almost contemporary translations do not depend on each other, a sign that the reception of the Sefer Yetzrah has been, from the outset, a plural and, above all, commented reception. Even the term sefirah, a key word in the history of kabbalah, which motivated, at least in part, the reception of the Sefer Yetzirah among Christians, with its enigmatic complement blimah has also been understood in divergent ways: Mithridate translates it, consistently, with numerationes sine aliquo ; Magister Isaac initially tried the more cautious transcription “sphiroth”, but has since resolved to translate it with proprietates preter ineffabile ; the anonymous translation (this time without marginal variants) renders it with a very decided option: numeri praeter id quod est ineffabile or also absque ineffabili. So Reuchlin, who perhaps already had Magister Isaac’s translation at his disposal, prefers to translate the expression Sefirot blimah with “numerationes praeter aliquid”. There would already be enough material for a very articulate discussion, but I prefer to examine other sources, to show that, even before the publication of the first printed translation of the Sefer Yetzirah, that of Guillaume Postel, published in 1552, i.e. a decade before de la princeps of the Hebrew text, which appeared in Mantua, in the glorious season of suspension of Hebrew printing in Venice that gave us so many firsts, among others to name only the most important, the Tikkune Zoharthe Ma’areket ha-Elohut and, of course, the two simultaneous editions of ZoharMantua and Cremona (1558-1560), even before the publication of the Liber Creationis by Guillaume Postel, other Christian authors quote from the Book of Formation, often attributing it to Abraham, such as the aforementioned Francesco Zorzi, who uses the Book of Formation throughout his works, normally attributing it to Abraham, even though he knows that some say the booklet was composed by Rabbi Akiva. In any case, the passages he quotes from it, either in the De harmonia mundi (1525), or in the aforementioned Problemata (1536), as well as in works that remained unpublished during his lifetime, such as theElegante Poemathe Commento sopra il Poema and in his Commentaire sur les thèses cabbalistiques de Pic dela Mirandole, do not conform to the translations we have just seen, but are the result of his direct engagement with the Hebrew text and with several commentaries, such as the particularly exquisite and rare one (he is the only Christian of the Renaissance and modern age to know it) entitled Meshovev Netivot by Samuel Ibn Motot and many others, particularly Mosheh Botarel’s, from which, alas, he takes many forged bibliographical references. 11 S. Campanini, Le fonti ebraiche del De harmonia mundi di Francesco Zorzi, in “Annali di Ca’ Foscari” 38,3 (1999), pp. 29-74; F. Zorzi, L’armonia del mondo, Bompiani, Milano 2010. It’s interesting to note that he translates the word sefirot with numerationes sive mensurae, giving a decidedly Platonic twist, under the influence of the commentaries he read in the original, but also integrating the Sefer Yetzirah into his conception of the unity of Christian, Jewish and pagan knowledge, in the form of a Ficinian, Hermetic and Neoplatonic synthesis. Reading the Sefer Yetzirah through Zorzi can sometimes give the impression of having discovered an improbable fragment of a Proclus, now Christian, who rereads the works of Pythagoras as if they had come from the pen of Plotinus. This is not to say that Zorzi’s interpretation is any more or less legitimate than any other, but to emphasize that the Sefer Yetzirah in the Renaissance can only be read with certain commentaries, and the translations rightfully belong to this genre.

With the publication of Guillaume Postel’s translation in Paris in 1552, this became evident even on the title page: To indicate that the book could be purchased from Postel himself, who had paid in full for the edition, we read the curious formula: “Veneunt ipsi autori, sive interpreti” i.e.: “on sale from the author, or, if you like, the translator (and commentator)”. There’s no better way to put it: translating the Sefer Yetzirah, whether into Latin or another language, means rewriting it every time. Postel published this translation when, as he says, he was six months old in his new life, everywhere he calls himself renatus or restitutus, having received a revelation from the Venetian virgin, Mother Jeanne, whom he had met in Venice in 1547, and who had set him apart with extraordinary revelations. This translation, though linguistically fascinating – for example, he translates sefer sfar sippur, noting that the three words are made up of ten letters, by numerans, numerus, numeratum, and blimah with “silentii” – was not too widespread and, because the author, to escape the tribunal of the inquisition, was declared insane, the translation itself, sprinkled with commentaries and prophetic a parte could only be judged, at the very least, idiosyncratic, did nothing to halt the production of other Latin translations which continued, before and after the publication of the one that goes under the name of Pistorius, but which is, as we have seen, the work of Magister Isaac, along with other translations, some of which were even published: one, still unpublished, is kept at the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan and belonged, if not to him, to Cardinal Federigo Borromeo: it may date back to the young Borromeo’s enthusiasm for the cabala in Rome towards the end of the 16th century, of which he tells a somewhat ashamed tale in his De cabbalisticis inventis of 1622. 12 S. Campanini, Federico Borromeo e la qabbalah, in “Studia Borromaica” 16 (2002), pp. 101-118. Another Latin translation, accompanied by the Hebrew text and a translation of part of Joseph ben Shalom Ashkenazi’s commentary on the 32 ways, is preserved at the BNF (ms. Hebr. 881). The ms. is undated and the only name that appears is that of a certain “Kefa mi-sela’ lavan”, which has been interpreted by Georges Vajda. 13 In the description of the Hebrew mss. at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, an unfinished project now available online. as Pierre d’Auberoche, who was a Jesuit and, curiously, like Postel, abandoned the order in 1621. This identification, though ingenious, is not correct, since we know nothing of d’Auberoche’s interest in alchemy and magic, and the ms. came from the Abbey of Saint Martin des Champs, where d’Auberoche would never have lived. What Vajda did not consider was the opinion of François Secret who, as early as 1964, had attributed ms. 881 to the pen of Pierre-Victor Palma Cayet (1525-1610). 14 F. Secret, Les kabbalistes chrétiens de la Renaissance, Dunod, Paris 1964, p. 191; according to Secret, Cayet’s pen is also responsible for the Hebrew mss. 882 and 1294; cf. also Id,Littérature et alchimie, in “Bibliothèque d’Humanisme et Renaissance” 35 (1973), pp. 499-531: 516-519(Pierre-Vistor Palma Cayet et l’alchimie); M. Yardeni, Esotérisme, religion et histoire dans l’oeuvre de Palma Cayet, in “Revue de l’histoire des religions” 198,3 (1981), pp. 285-308. On the basis of the paleography, there is no doubt that this manuscript was written in the 17th century and that it bears witness to another direction of interest in the Sefer Yetzirah on the part of Christians or non-Jews from that time onwards, which will underpin the spread of the Sefer Yetzirah in translation until the present day, I refer to the book’s status as a basic treatise on the practice of magic, which, along with instructions on how to make a golem, could already be found in the commentary by El’azar of Worms, translated, as we have seen, by Mithridate for Pico della Mirandola. 15 S. Campanini, El’azar da Worms nelle traduzioni ebraico-latine di Mitridate per Pico della Mirandola, in M. Perani – G. Corazzol (édd.), Flavio Mitridate mediatore fra culture nel contesto dell’ebraismo siciliano del XV secolo. Atti del convegno internazionale di studi, 30 giugno-1 luglio 2008, Officina di Studi Medievali, Palermo 2012 pp. 47-80. Two Latin translations of the Sefer Yetzirah also appeared in print in the 17th century, and it’s curious to note that both are also accompanied by the original Hebrew text, a clear sign of the fact that the translation, precisely like the commentary, cannot advance the ambition of substituting for the text, being merely an aid for returning to the text and meditating on the obscure rhythm of its enigmatic propositions. I refer, as is obvious, to the famous Latin translation by the Jewish convert Stephanus Rittangel, published in Amsterdam in 1642, which is also accompanied by a translation of the Pseudo-Rabad commentary and a Latin commentary in which Rittangel shows his knowledge of the literature of medieval commentaries, no less than the theological problematics of his time, especially the great question of anti-trinitarianism, which remains one of his most obvious preoccupations in this and other of his works. According to bibliographers Julius Fuerth and Moritz Steinschneider, an alternative translation would be the one contained in the Oedipus Aegyptiacus (volume II,1) by the German Jesuit Athanasius Kircher, published in Rome in 1653. In reality, there are only extracts and, as David Stolzenberg has shown, 16 D. Stolzenberg, Egyptian Oedipus: Athanasius Kircher and the Secrets of Antiquity, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago – London 2013, p.. 166. everything Kircher knows about the Sefer Yetzirah and especially the Pseudo-Rabad commentary comes directly from Rittangel, who is never quoted, one might think because he was a Lutheran, but this often happens to the German Jesuit, for example in the case of Paulus Riccius, whom he uses extensively, and who was, although a convert, a good Catholic. By studying the three versions (two complete and one, Kircher’s, in extracts), I was able to verify that Pierre-Victor Palma Cayet does not depend at all on Rittangel’s version, as soon as he translates the three

In retrospect, I think I’ve shown, albeit briefly and in excerpts, that every Latin translation – but this could have been true of every later linguistic tradition, with or without commentary – is in itself a commentary, and obviously denounces an interpretation, a choice, in other words, a way of reading the Sefer Yetzirah. As for the original, it remains closed, despite so many interpretations, in its fascinating laconism. But the apparent impasse may not be the last word. In commenting on a book that is no more than three or four pages long, but contains a small portable cosmogony, and which resembles almost nothing, although it recalls many other books, it is perhaps well advised to try to let it have its say : which is immediately possible with an edition or manuscript that also contains the original, which is the source and purpose of every translation: ואם רץ לבך שוב למקום ( we-im ratz libbekha shuv la-maqom), si labitur cor tuum redi ad locumand if your heart fails (or: if it runs), return to the place. This passage has often been interpreted as an exhortation to return to the unity of the Place par excellence, but, remembering the fulminating to-and-fro of angels, who can be seen as translators, as soon as they strive to convey a message, some of the manuscripts here present the variant: למקום שיצאת ממנו(la-maqom she-yatzata mimmennu): in the place from which you came out.